I know, I know, I haven’t been writing. While it’s true that I haven’t been giving you a bad deal for your money (as everyone reading this has paid $0.00 for the privilege), I made an implicit commitment when you signed up that I would be writing at some kind of regular schedule and I haven’t adhered to it. I’m sorry.

That all being said, there has still been a trickle of new sign-ups and even emails from readers, all of which I really appreciate. If you like what you read, please subscribe or share it and, as always, feel free to email me at matthew.zeitlin@gmail.com about whatever.

What are the Biden administration and Federal Reserve trying to do right now?

If you read the Fed’s latest statement, the goal of monetary policy is to “to achieve maximum employment and inflation at the rate of 2 percent over the longer run,” and keeping in mind that inflation has been under that target for years, it will aim to “achieve inflation moderately above 2 percent for some time so that inflation averages 2 percent over time.”

The Fed has projected that it will keep interest rates at near zero through the end of 2023, when they expect the economy will be growing at over 2 percent a year (after 6 and 3 percent growth in 2021 and 2022) and that inflation will be a hair over 2 percent.

The Biden Administration’s job is to actually make this happen. When Democrats swept the Georgia runoff senate elections in December, Goldman Sachs upped its 2021 growth by half a percentage point, from just below 6 percent to almost 6.5 percent. These projections paid off when the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan passed the Senate by one vote, with its barrage of direct payments, aid to states, bolstering social insurance programs and all the rest.

What the markets see is the Federal Reserve, Congress, and the White House all rowing in the same direction on fiscal policy and, almost as importantly, doing so with a credible commitment to continue moving in that direction for at least two years, or until a Democratic senator from a state with a Republican governor trips and falls.

Some have been suggesting that this is a major break — with neoliberalism, with austerity, with Democratic deficit squeamishness and so on and so forth. What I want to suggest is that what the market saw was a continuation of a framework established by Democrats in Congress, Powell as the Fed Chair and, yes, Donald Trump as President (and, Steve Mnuchin as Treasury Secretary).

When Donald Trump came into the White House, both liberal and nonpartisan observers thought the economy might be at or near full employment. At the time, the unemployment rate was was a hair under 5 percent, inflation was a bit under 2 percent, the employment-to-population ratio for prime-age workers was 78.2 percent.

Up until the Covid-19 Crash, the employment indicators moved in the right direction while inflation stayed around or below 2% .

Why did this happen? For one, there was more slack in the economy than conventionally assumed, meaning that unemployment could continue to fall without pushing up prices too much. Second, the government, starting on the fiscal side, was an active participant in keeping things moving.

Deficits continued to expand during the Trump years, even as economic growth should have pushed up tax receipts and tampered down usage of safety net programs. There’s no mystery as to why this was happening.

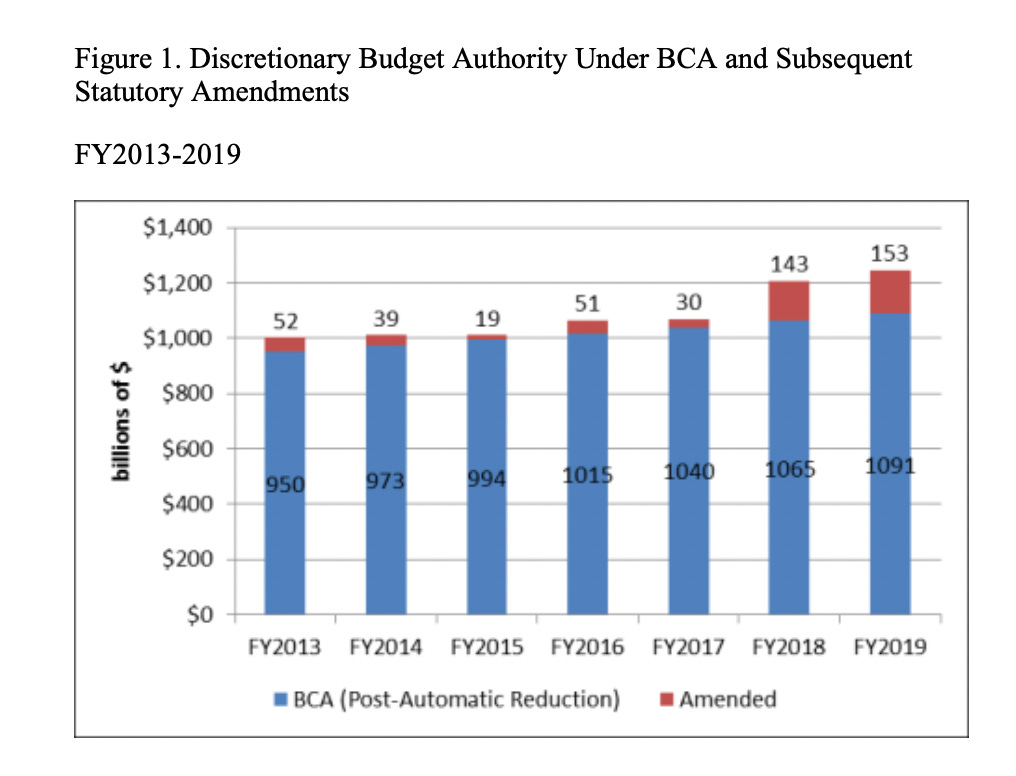

There was over $1 trillion worth of tax cuts agreed to at the end of 2017 and, maybe even more importantly for short turn economic growth, the White House and Congress found themselves easily able to agree on spending bills that scrapped caps agreed to by the Obama administration and Congressional Republicans and boosted discretionary spending by even more than previous spending bills had.

It was hard for Barack Obama and Paul Ryan to agree on government spending levels that will make both of them happy; it’s pretty easy for Steven Mnuchin and Nancy Pelosi to do so. Democrats are more than happy to let Republicans spend money on the military and keep popular projects funded in exchange for keeping funding for Democratic priorities on an even keel.

The coup de grace was when, after some jostling and jawboning from our former President, the Fed started cutting rates in the summer of 2019 and came around to its new “average inflation targeting” a year later.

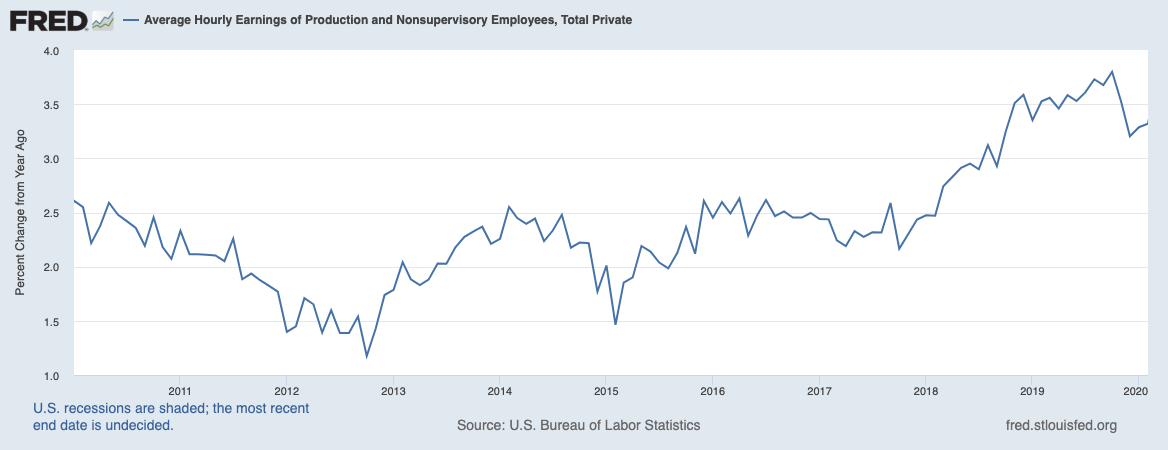

So by 2019 and early 2020 all the pieces were in place: the government was pushing money into the economy with fiscal policy and the Fed wasn’t raising rates. The results were starting to show up — not only were the employment statistics moving in the right direction, but the wage numbers were as well, with wage growth getting over 3%.

The rest is history. Unemployment skyrocketed, Mnuchin and Pelosi mobilized to spend trillions, flushing so much money directly to households and especially to the unemployed that personal income actually went up during one of the sharpest economic downturns in modern human history. Thanks to the Georgia runoff victory, Democrats were able to keep the party going even as Republicans discovered their dormant deficit hawkery.

There have been some major shifts in how policymakers think recently — the Powell Fed explicitly embracing above 2% inflation if it’s necessary to get to maximum employment, the move towards cash benefits, the sheer scale of the Covid rescue plans — but the grand ideological declarations are following what’s happening on the ground in the grubby conjunction of electoral politics, presidential personality, and macroeconomic reality.

“Let’s go back to 2019 or even very early 2020 — forever, or at least through a business cycle” may not sound like the announcement of one world dying and another being born, but perhaps the world-spirt no longer rides on horse back; instead we may need to, like our former Treasury Secretary, adjust our lenses to see what’s already there.

Good to hear from you!